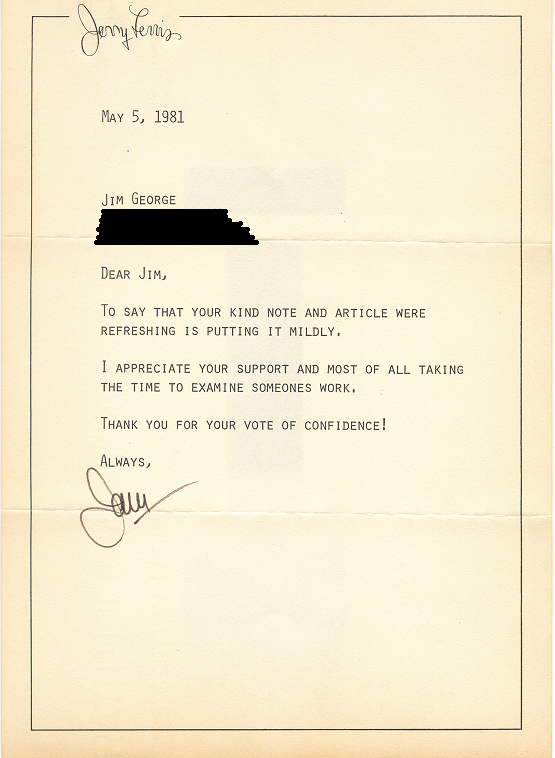

(In 1981 I wrote a newspaper profile on Jerry Lewis and subsequently sent him a copy. Not long afterward, I received a personal letter of thanks from him. This is the original article.)

Genius is childhood recalled at will.

–Baudelaire

If Baudelaire’s definition holds even a speck of truth, therein lies the clue to the European view of Jerry Lewis as a comic genius on par with Chaplin.

“I’m 55, but I’m really nine,” said Lewis in a recent Tomorrow interview. “The key to my whole lifestyle is mischief, and I cannot, as a 55-year-old man, really think mischievously because that demeans my being. But there’s nothing wrong with a nine-year-old thinking that way. I cherish that nine-year-old because he’s everybody. He keeps me young. He keeps me thinking young. He’ll be at my next birthday, and he’ll have the most fun.”

Jerry’s kid, that mannish boy who has bumbled, mumbled and mugged his way through more than 40 films, is about to return to the silly screen for the first time in a decade in Hardly Working, which opens this week. Like it or not, the film buffoon is back.

The French toast Lewis’ comic brilliance. Director Jean-Luc Godard expressed his admiration to an incredulous Dick Cavett not long ago. But in America, there’s a split-decision. Statesiders generally find his juvenile Jerry-atrics either hysterical or grating. And it is the red, white and bluenosed critics who are Lewis’ most vicious detractors.

The reason for the animosity may be simple enough. Like Peter Pan, that impish, jerky, wonder-struck little kid who resides in the body and soul of Jerry Lewis has never aged. Therefore, he has remained unshackled from the rites, wrongs and constraints of society. On one level, he represents freedom. People not so free, people squeezed into role-modeled behavior, people who act the way society says they ought to act are likely to feel threatened by that kid and the freedom he represents. Hence, the jeerleaders.

Lewis’ self-imposed 10-year stretch away from filmmaking was provoked by some overexposure of flesh flicks in the early ‘70s. When the cinematic tide turned from boffo to porno, Lewis took a cab.

“I love the film industry,” he told Tom Snyder. “I took it as a personal affront that they were getting shabby. And it happened with a film I made for Warners, Which Way to the Front? a film I was really in love with. I put two years of a lot of blood and a lot of sweat into it.”

The skin-toned times created a condition which shocked Lewis out of his director’s chair—and right out of the industry. Driving by a theater one disenchanted evening, he spotted the marquee which had double-billed Which Way to the Front? with Deep Throat. That odd coupling resulted in Lewis’ giving Warner Brothers a shouting-room only performance of Hellzapoppin’—sans jokes and music. But the Warner Brotherhood had a cop-out: they were so involved with their then-smash Woodstock that they gave the distribution rights of Lewis’ film to other companies.

“Well, I don’t want to know from explanations,” said Lewis, “’cause I was shattered by it. In the mail I got, I was the heavy. The mothers and fathers were writing me, ‘You are someone we allow the children to go to see, and you have a responsibility’ and all that jazz. And I got really turned off, really cold.

“Now the capper was Dick Zanuck comes to see me and he wants me to direct and star in Portnoy’s Complaint. I said, “Dick, that’s not my style. I don’t think I know how to make that kind of film.” Then I got a script where they wanted me to play a homosexual who had committed matricide.

“I said, hey, let me get back to Vegas. I’ll play concerts, I’ll go back to The Palladium in London, I’ll do my thing. And I said it’s got to turn. If it doesn’t turn, at that point I really didn’t ever want to make a film again. And it did turn, starting in ’78.”

Jerry Lewis has always been a G-man; family-oriented films have always been the Lewis trademarquee. Yet, despite all those Jerry-vanilla comedies, he is not about to march behind that other Jerry, the pulpit politico Rev. Falwell, and wage war on pornography. (That would make a hilarious scene, though: the unsure-footed stumblebum Lewis character traipsing behind the preacher like a spastic marionette, yelling in that chalk-screechy voice, “Hey wait for me, Mr. Fellman! Uh Rev. Failsafe! I’m comin’ Rev. Fallout!”)

“I don’t believe in censorship,” said Lewis. “If you want to see a porno film, an audience should have a place to go see it. But it’s a little incongruous and it’s hardly sensible to run Bambi with The Devil in Miss Jones just for the sake of Barnum and Bailey showmanship. The theater should run The Devil in Miss Jones for that audience, but leave Bambi where it belongs. It’s that simple.”

As Lewis hoped, the packaging of flesh and funny bone was a short-lived phenomenon which, he said, “had probably the same chance that the Edsel did, thank God.”

In spite of his predilection for tomfoolish behavior, Lewis is a slapstickler for professionalism. As a director, writer and actor, he takes his comedy seriously. He doesn’t suffer fools gladly—or any other way. He said, “I hate incompetents. I get very difficult when somebody shouldn’t be in the job they’re holding because they’re keeping it from a man who’s qualified. Moreover, they’re contagious. They’ll run through your crew, and they will dismember that crew.

“I’m making a film that I hope one day my great-great-grandchildren are gonna see. They’re gonna examine my work, and the fabric and character of this man is gonna be up for grabs. I’m not havin’ some moron on the set looking at his watch yawning ‘cause it’s just a job. He’s outa there. That’s only happened twice in 41 films.”

Lewis’ upcoming attractions include roles in Martin Scorsese’s drama, The King of Comedy (which also stars Robert DeNiro), and the screen-bound adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slapstick, being directed by Lewis disciple Steven Paul.

The Day the Clown Cried, Lewis’ own dramatic film (his sole to date), has been gathering Swedish dust, along with two Ingmar Bergman films, since 1973. Like the Bergmans, it was shot in Sweden as a Swedish-French co-production. When the political deal soured, the films were stopped dead in their soundtracks. A Godard picture, also part of the (mis)deal, was similarly thrown a French curve and lies in limbo in his homeland.

“They tell us,” Lewis said, “that this year, it looks like they’re gonna make nice with one another, and we can all finish our films.”

However, for the present, comedy comes first. Sight-gagging and language-mangling are back in vogue, and the maestro has returned to show ‘em all how it’s done. Hardly Working has Jerry Lewis heartily working. Maybe he is 10 years older. But that kid is still nine.