Picture yourself in a boat on a river

With tangerine trees and marmalade skies

Those lyrics from The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” a song directly inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, partially conjure up the scene which provided the genesis and revelation of what has become The Bible of so-called nonsense literature, a work which more than a century and a half later still influences prose, poetry, art, music and film.

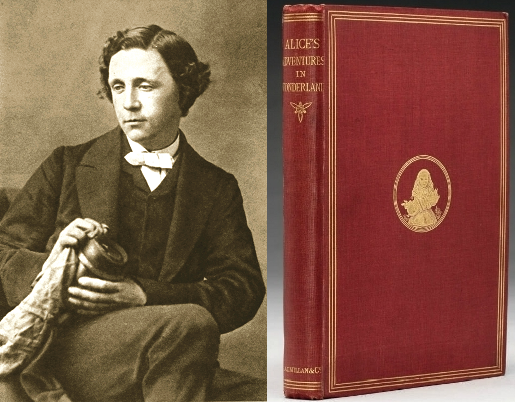

There were no tangerine trees on the English shores on July 4, 1862 when Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, his friend Robinson Duckworth, and the three little Liddell girls—Alice, Edith and Lorina—went for a boat ride.

And whether the sky was marmaladen with clouds is debatable (the author described it as a “cloudless day,” but meteorological records indicate that it rained on the date in question).

Whatever the reality, on that tranquil “golden afternoon,” as Dodgson termed it, he ad-libbed a wondrously nonsensical tale of a girl named Alice who fell down a rabbit-hole. At the non-fictional Alice’s behest, Dodgson was obliged to recollect the story and commit it to manuscript so that she could make the return trip over and over again with her namesake.

Although the final version wouldn’t materialize until some three years later, it was on that fateful July day that Dodgson, tuned into the gods and inspired by the presence of his friends, planted the seed of the story which would give him an immortality he never dreamed of.

Its first incarnation was Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which he illustrated himself. Later, he added more material and new characters (The Cheshire Cat, The Mad Hatter), commissioned artist John Tenniel to do a new set of drawings, rejected the earlier title for sounding “too like a lesson book about mines,” and the fairy tale became the celebrated Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865.

“In writing it out,” explained Lewis Carroll, Dodgson’s author alias, “I added many fresh ideas which seemed to grow of themselves upon the original stock; and many more added themselves when, years afterward, I wrote it all over again for publication; but…every such idea, and nearly every word of the dialogue, came of itself.”

Carroll cast himself and the other boaters in his magical tale. The Duck was an animalization of his pal Duckworth; The Dodo, Dodgson himself—in a self-deprecating jab at his own lifelong stammer (Do-Do-Dodgson) which, interestingly, vanished in the company of children; The Lory and The Eaglet, Lorina and Edith respectively; and, of course, Alice was Alice. In name and inspiration only, however.

“…Alice Liddell is not the character in the books,” wrote Jean Gattegno in Fragments of a Looking-Glass. “At most we can say that some kind of current passed through Alice Liddell and brought to life a picture waiting to become animated.”

Choosing one of four pen-names the author submitted to him, Edmund Yates (editor of Comic Times and The Train, a pair of publications for which Carroll wrote on occasion) christened Dodgson, Lewis Carroll. He might just as easily have been Edgar Cuthwellis, Edgar U.C. Westhill or Louis Carroll, the other names under consideration.

Both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its equally enchanting sequel, Through the Looking-Glass (1871), incorporated unfinished bits and piecemeal ideas Carroll had written years earlier. The first verse of the poem “Jabberwocky”—which Derek Hudson called “the ‘Kubla Khan’ of nonsense”—from Through the Looking-Glass is one such example.

Like Edward Lear, Carroll often invented his own language, and both authors’ words’ worth was primarily in their sound and meter. However, while Lear’s creations were purely nonsensical nonsense, if you will (or even if you won’t), Carroll frequently had a method to his mangling:

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogroves

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Unlike other welders of words, e.g, James Joyce—who let it up to his readers to fathom the meaning of his newfound language—Carroll bothered to relate, right there in his book, via the mouth of the on-and-off-the-wall Humpty Dumpty, how and why he put a little english on his English.

“I can explain all of the poems that were ever invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet,” proclaims the famous Eggman to Alice.

“Slithy” is a fusing of “slime” and “lithe,” “gimble” is to “make holes like a gimlet,” “Mimsy” is a compound of “miserable” and “flimsy,” “mome” is a contraction of “from home,” as “wabe” is of “way before” and “way behind.”

Similarly, “chortle,” from elsewhere down the lines of “Jabberwocky,” is a blend of “chuckle” and “snort,” and it is but one example of Carroll-coined words that have become assimilated into our everyday language, as any dictionary will attest.

Wrote Gattegno, “…While continually stressing the difference between the meaning intended and the meaning understood, and showing how words are empty forms that one can play about with and not worry about the ‘sense’ one may arrive at, he also makes the word the basic unit around which the whole universe of significance comes into being. Words, which he does his best to destroy (with puns, plays on words, word games, etc.), also take on a certain almost magical value as objects of supreme enjoyment.”

“Alice in Wonderland broke new ground,” wrote Derek Hudson in Carroll, “because it was in no sense a goody-goody book but handled childhood freshly and without sententiousness.

“The nearest parallel to the humorous method of Lewis Carroll is probably that of The Marx Brothers, whose dialogue not only has many verbal similarities with his, but who also, like him, assert one grand false proposition at the outset and so persuade their audiences to accept anything as possible…Both have been based largely on a play with words, mixed with judicious slapstick, and set within the framework of an idiosyncratic view of the human situation; their purpose is entertainment. Lewis Carroll has one transcendent advantage—with his limpid prose, he paints the color of poetry.”

And Carroll was, after all, above all, a poet. Continued Hudson, “He was, indeed, perhaps the most poetic when he wrote in prose, and we must think of the Alice books, with their harmonious and unforced blending of prose and verse, as being primarily a poetic achievement.”

Despite his fame and good fortune, Charles Dodgson struggled to keep his pseudonymous alter ego a separate entity. Dodgson was a mathematician, a logician, and a don at Christ Church at Oxford, England; Lewis Carroll existed only when tucked under the covers of his dreamlike books.

“I cannot, of course,” stated Dodgson/Carroll, “help there being many people who know the connection between my real name and my ‘alias,’ but the fewer there are who are able to connect my face with the name ‘Lewis Carroll,’ the happier for me.”

Such sentiments were not merely aw-shucks idol chatter from a humble soul; besides publishing a leaflet in which he “neither claims nor acknowledges any connection with any pseudonym, or with any book that is not published under (his) own name,” he returned to senders all letters addressed to “Lewis Carroll.”

In Lewis Carroll and His World, John Pudney wrote, “Lewis Carroll has been described as the best photographer of children in the 19th century…Children were of course the inspiration for his most creative work, both in literary and photographic terms…(He had a) penchant for the company of pre-pubescent girls and situations which would now trendily be associated with a Lolita syndrome.”

Not a book has been written about Carroll, it seems, which hasn’t in some measure touched on (no pun intended—for a change) those young girls, who seemed to be the joy of Carroll’s life. Alice was neither the first nor the last.

Speculation and Freudian interpretations aside, what we do know as fact is A) He loved to spend time with females aged anywhere from, say, four to puberty (though in later years, he seemed equally delighted by older young women—up to 17 or thereabouts); and B) He loved to photograph them–with their parents’ permission–in the nude.

“In the last three decades of Victoria’s reign,” wrote Pudney, “photographs of children in the nude, and voluptuously fleshy paintings of naked adults, were not only acceptable but fashionable. Carroll’s portraits sans habillement were neither a novelty nor necessarily an outrage.”

Much ado about nothing on? His photo-graphic hobby and/or his attachment to his subjects reportedly incurred mom wrath on more than one occasion, but while there has been no incriminating evidence against the man, the debate as to his true nature and motivations goes on.

Though violence creeps into the Alice books (“Off with their heads!”) Carroll was a gentle man who despised the degradation of women and was vehemently anti-vivisection and anti-hunting for sport with its happiness-is-a-warm-gun mentality. In a pamphlet he once wrote, he predicted a future “when the man of science, looking forth over a world which will then own no other sway than his, shall exult in the thought that he has made of this fair green earth, if not a heaven for man, at least a hell for animals.”

On the flip side, Carroll was said to be extremely class-conscious and decidedly self-centered, somewhat of a prima don. As Pudney stated, “He just never did anything much that he did not want to do or felt that duty called upon him to do.”

Carroll’s other literary works, which include “The Hunting of the Snark,” “A Tangled Tale,” “Sylvie and Bruno,” “Sylvie and Bruno Concluded” and “Phantasmagoria,” showcased his genius in varying degrees, though none of them eclipsed or matched the pair of Alice books.

Virgina Woolf wrote of Carroll, “(Childhood) lodged in him whole and entire…He could do what no one else has ever been able to do—he could return to that world: he could recreate it, so that we too become children again…The two Alices are not books for children, they are the only books in which we become children…”

Lewis Carroll was, in the best sense, kidding us.

(Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jim George and byjimgeorge with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.)